10 min to read

Python - Writing functions - scope of variable

This article is a part of the Python - 101 series, you can access the full version of the series here:

-

Coding 101

-

Writing functions in Python

- Basic

- Scope of variables (you are here!)

- More on arguments and lambda functions

- Best practices

-

Control flows in Python

-

Errors and exceptions

-

Classes

Welcome to the fourth article of the Python - Coding 101 series, after reading this article, you’ll learn:

- What is scopes

- How to specify which scope you are referring to

Through this article, we have talked about the definition and the importance of functions in programming, and how to declare a function. Today we will talk about how to make your function even more robust and flexible using scope.

1. Variables in Python

Firstly let’s go through the definition of variable in programming. A variable is a label or a name given to a certain location in memory. This location holds the value you want your program to remember, for use later on.

So important thing to note here: variable does not hold the value you defined, the location in memory does.

To create a new variable in Python, you simply use the assignment operator (=, a single equals sign) and assign the desired value to it. A rule of thumb is that the variable name must be on the right hand side of the assignment operator, while the desired value must be on the right.

example_var = 1

Python has some rules that you must follow when creating a variable…

- It may only contain letters (uppercase or lowercase), numbers or the underscore character

_. - It may not start with a number.

- It may not be a keyword (you will learn about them later on).

You can try initializing a variable named 1example_var to see for yourself.

2. Scope of variables

To better understand scope of variables, let’s consider this example:

def print_var():

var_name = 1

print(var_name)

print(var_name)

In this function, we did not give it any arguments and we assign 1 to the variable var_name inside the function. Now try print(var_name) outside the function, what would you expect the screen to display?

That function calling in Python will give you an error, like this:

---------------------------------------------------------------------------

NameError Traceback (most recent call last)

in

3 print(var_name)

4

----> 5 print(var_name)

NameError: name 'var_name' is not defined

Python doesn’t know what var_name is, kinda strange right, since you have already defined it inside the function print_var(). Turns out there is a thing in Python called scope of variable that explain this kind of behavior.

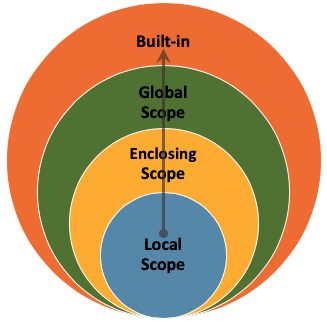

Scope defines in which part of a program a variable is accessible. There are four major types of variable scope and is the basis for the LEGB rule. LEGB stands for Local -> Enclosing -> Global -> Built-in. Note that variables that exists in the outer scope can be accessed in the inner one.

Python follows the rule of LEGB.When you call variable inside a function, Python first look if “x” was defined locally within such function. If not, the variable defined in the enclosing function. If it also wasn’t defined there, the Python interpreter will go up another level - to the global scope. Above that, you will only find the built-in scope, which contains special variables reserved for Python itself.

2.1. Local Scope

Whenever you define a variable within a function, its scope lies ONLY within the function. It is accessible from the point at which it is defined until the end of the function and exists for as long as the function is executing. In simpler terms, value of variables defined inside a function cannot be changed or even accessed from outside the function. The example above shows exactly what local scope is. var_name is defined in the function print_var(), so it cannot be access outside of the function. This is because var_name is “local” to the function - thus, it cannot be reached from outside the function body.

var_value = 1

def change_var(value):

value = 5

change_var(var_value)

print(var_value)

In this example, we modified the value of var_value inside the function change_var(). Can you guess what the the print(var_value) return? You can see that print(var_value) return 1, the original value of var_value, as if the function does not have any effect on the variable. This is because value of the var_value is modified within the local scope of the function, which does not affect the real value of var_value in memory

How to specify variable from local scope: You don’t need any special arguments to specify that you are calling a variable from local scope.

2.2. Enclosing (Non-local) Scope

Do you know that we can define a function inside a function? In Python, it is called a nested function.

def outer():

first_num = 1

def inner():

second_num = 2

# Print statement 1 - Scope: Inner

print("first_num from outer: ", first_num)

# Print statement 2 - Scope: Inner

print("second_num from inner: ", second_num)

inner()

# Print statement 3 - Scope: Outer

print("second_num from inner: ", second_num)

outer()

Try running that function in your console, got an error?

From this example, you can notice 2 things:

- The print statement 3

print("second_num from inner: ", second_num). That is the place where your function fails, becausesecond_numis defined withininner()scope. - The print statement 1

print("first_num from outer: ", first_num)did not raise any error, even iffirst_numis not defined explicitly insideinner(). This is because the scope offirst_numis larger, it is withinouter(). This is an enclosing scope - a special scope that only exists for nested functions. If the local scope is an inner or nested function, then the enclosing scope is the scope of the outer function

How to specify variable from non-local scope: You will need to specify the argument nonlocal variable_name to modify or change its value before calling that variable. For example:

def outer():

first_num = 1

print("first_num from outer before change: ", first_num)

def inner():

nonlocal first_num

first_num = 5

second_num = 2

print("first_num from inner: ", first_num)

# Print statement 2 - Scope: Inner

print("second_num from inner: ", second_num)

inner()

# Print statement 3 - Scope: Outer

print("first_num from outer before change: ", first_num)

outer()

which give this output:

first_num from outer before change: 1

first_num from inner: 5

second_num from inner: 2

first_num from outer before change: 5

If you remove the line nonlocal first_num, the output should be:

first_num from outer before change: 1

first_num from inner: 5

second_num from inner: 2

first_num from outer before change: 1

It is clear that when we nonlocal first_num, modifying the value of first_num when calling the inner() function, the value of first_num in the non-local scope if changed too. That is not the case without nonlocal first_num.

2.3. Global scope

Whenever a variable is defined outside any function, it becomes a global variable, and its scope is anywhere within the program. Which means it can be used by any function.

congrat = "Congratulation"

def greeting_name(name):

print(congrat, name)

greeting_name("Aiden")

Output:

Congratulation Aiden

How to specify variable from global scope: You will need to specify the argument global variable_name to modify or change its value before calling that variable. For example:

congrat = "Congratulation"

def greeting_name(name):

global congrat

congrat = 'RIP'

print(congrat, name)

greeting_name("Aiden")

which give this output:

RIP Aiden

2.4. Built-in Scope

This is the widest scope in Python! All the special reserved keywords fall under this scope. We can call the keywords anywhere within our program without having to define them before use. These include:

You need to avoid these keywords when defining your variable. Even if you insisted, Python will raise an error.

False = 1

File "", line 1

False = 1

^

SyntaxError: can't assign to keyword

3. Exercises

As an exercises for scope of variables in Python, try writing a function that take the power as an argument and return another function that take a number as an argument. For example:

# Assume the name of the outer function is power_raise.

# Calling power_raise(2) will create an another function that squares a number

square = power_raise(2)

# Calling square(3) will equal calling the function 3**2, resulting in the number 9

square(3)

Comments